Hollywood isn't smart enough to do racebending

Or a rant on the remakes of Lilo & Stitch, Harry Potter, and more.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably heard about the live-action Lilo & Stitch. The trailer debuted a few days ago and online outrage ensued about the appearance of Nani Pelekai, Lilo’s older sister. Namely, that half-white, half-Filipina actress Sydney Elizebeth Agudong appeared to have a tanned appearance to more closely match the animated Nani’s skin tone. This was done in lieu of, you know, just casting an actress that actually is this color.

It would be one thing if Disney cast a native, monoracially Hawaiian actress that happened to have light skin. People, myself included, would still quibble about the choice to lighten Nani’s skin tone and the implications of that, but they could at least say the film tried to honor the original in some way. But not only did Disney not cast a native Hawaiian actress, they cast one that is only half Asian entirely, and not even the right Asian at that. I’d laugh if this were simple incompetence, but “close enough” casting is too common in Hollywood for me to believe the choice wasn’t intentional. Close enough is not enough. But this is the logic of “racebending,” the practice in media of casting actors whose race is not consistent with the canonical character they are set to portray in a remake or adaptation.

The casting choice for Nani blew me because the animation of the Pelekai sisters was so striking in the original film. They were one of the few Disney films in the early 2000s to feature darker-skinned girls as protagonists. They joined Princess Jasmine and Pocahontas as main characters that maybe wouldn’t pass a paper bag test. They were so unambiguously indigenous to Hawaii; there’s no way you could have watched that movie and thought, “Ah yes, they’re tan for the summertime!” Their skin was beautifully deep with red undertones naturally, just like the other Hawaiian characters in the movie. Not only that, but Lilo and Nani had wide noses as real native Hawaiians do. In short, accuracy in phenotype was the one aspect of Lilo & Stitch that made it distinctive and, for its time, subversive among its peers.

Seeing a light skinned actress nearly brownface herself to play Nani makes my teeth itch because I have very little faith that Disney considered how the choice would impact the believability of the story. Bluntly, a light skinned woman like Agudong is less likely to find herself entangled with CPS than the original Nani would. Colorism dictates that the lighter your skin, the closer you are to whiteness, and thus your proximity to that whiteness affords you more privileges under systemically racist systems. The same goes for your facial features: smaller lips, slender noses, and bigger eyes (in the case of Asian folks) are prominent amongst Europeans, and therefore deemed conventionally attractive.1 Agudong fits in both categories.

There is plenty of data on the overrepresentation of Black children in the foster care system, proving that race does play a factor. For Hawaii specifically, native Hawaiian children are disproportionately more likely to end up in foster care compared to white and other ethnic Asian kids. So when you have a woman who is both white and other Asian (i.e., privileged) cosplaying a native Hawaiian, her character’s struggles with CPS immediately feel stilted and unbelievable. Even as a child, I felt the danger that an 18-year-old like Nani faced was realistic, because I could see my family members in her and knew of others who faced (or were victims of) similar state intervention. I simply don’t buy a wasian, conventionally pretty girl to be the target of hostility or investigation by CPS.

Lilo & Stitch is far from the first film where liberties were taken with the brown characters at the heart of a story. The original live-action Avatar: The Last Airbender (2010) was heavily criticized for casting white people as the very-obviously-non-white characters of the animated series. Let us not forget as well when Scarlett Johansson stood ten toes down to defend her starring role as a decidedly Japanese woman in Ghost in the Shell (2017). These controversies certainly contributed to casting directors putting forth marginally more effort in accurate casting for remakes; that’s why we have Asian diasporic actors in live-actions like Lilo & Stitch, Avatar (the Netflix series) and Moana. Strides are being made, however we must remain vigilant when such blatantly inaccurate casting choices are made for key roles.

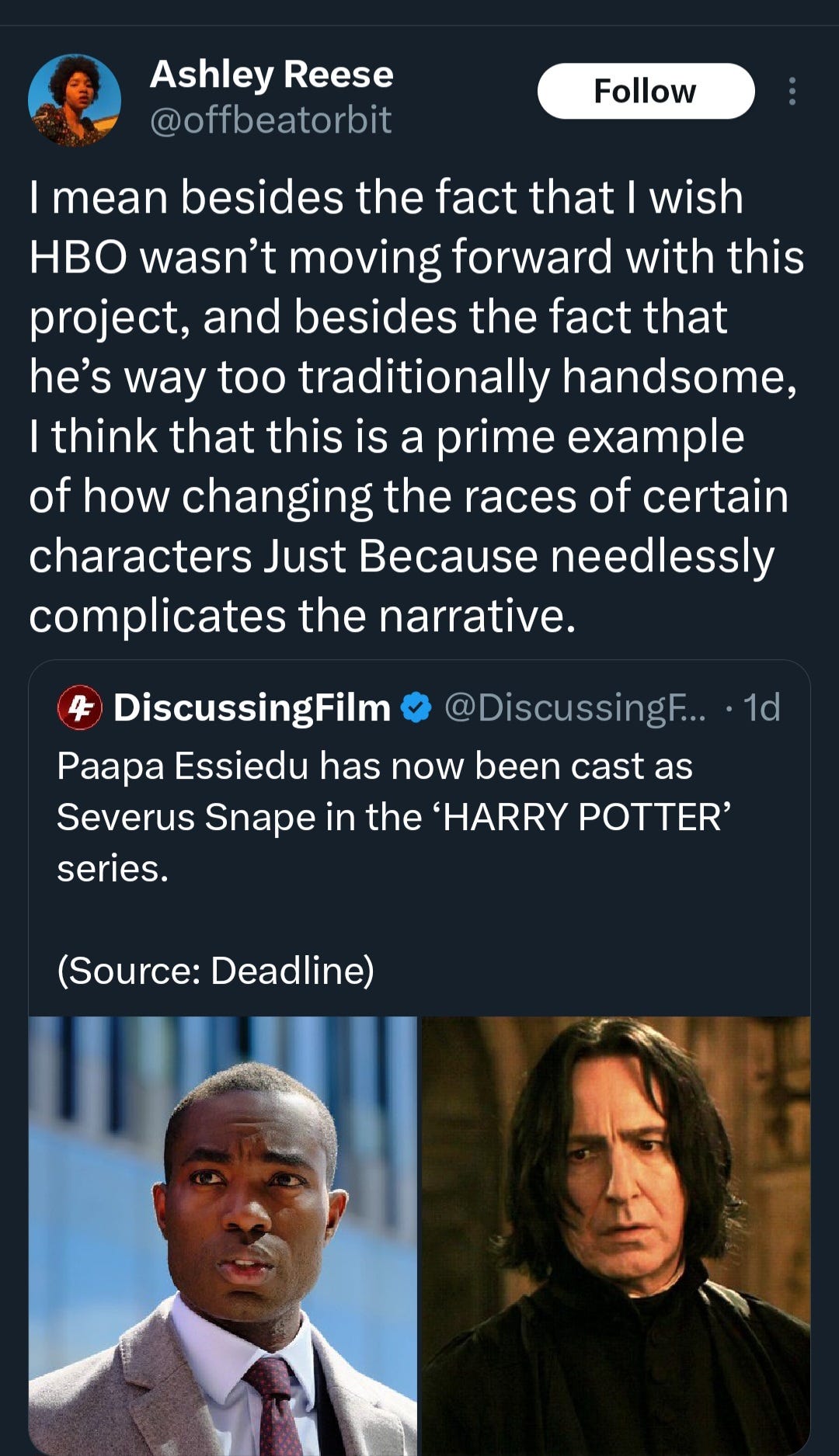

Speaking of inaccuracies, news of a puzzling casting choice for the Harry Potter HBO series recently broke. A Ghanaian British actor, Paapa Essiedu, was cast as Severus Snape, famously portrayed in the films by Alan Rickman. Normally, I am excited when Black actors are cast in canonically white roles in iconic franchises. Quvenzhané Wallis as Annie, Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury, and most recently Halle Bailey as Princess Ariel. None of these characters needed to be white in order for their respective stories to make sense, and Blackness brought flavor to each one that a white actor simply could not.

However, in the case of Harry Potter, many (non-white!) fans have argued that racializing the specific character of Snape adds layers to his backstory that may come across needlessly racist. “Needlessly” because race is an issue that the HP series has a tepid relationship with at best. Given that World Renowned Bigot J.K. Rowling is still involved with the series, the likelihood of the show addressing the racist undertones of James Potter and his friends bullying a Black boy with any sort of nuance is very low.

There’s also the optics of Snape as a Black man snarking at a white boy throughout the course of the series, even if we do find out he was actually on Harry’s side the whole time. Contentious interactions between Black and white people in the ‘70s and 90s are something that can’t simply be glossed over. The series is not out yet, so there’s still a chance the writing may address race in ways the original book and film series did not. In this political climate, though, I just can’t have faith in that.

Ultimately, I am bothered by these casting choices because in all of them, it is the non-white person’s experiences that are unconsidered. Not every story is universal; not every experience is one-size-fits-all. Filipino culture is not the same as Hawaiian culture. It carries meaning when a white boy picks on a Black boy rather than a white one. Racebending fails when the racial interplay between actors and their characters are treated as separate rather than symbiotic.

Those of you tapped into awards season likely saw the trainwreck that was Emilia Perez’s entire press run and awards campaign. A film made by French people set in Mexico starring multiple Latino-but-not-Mexican actors, Mexicans were understandably displeased with the film. They complained about the flippant depiction of Mexican culture, and indifference toward the country’s people while promoting the film. After winning her Oscar, Zoe Saldana — herself not unfamiliar with racial controversy with her previous role as Nina Simone2 — went mask off in the press room when addressing Mexican criticism of her film. She said that, despite the film taking place in Mexico and featuring Mexican characters, it was not a film about Mexico.

In a literal sense, sure, Emilia Perez may not have been a film about Mexico. Most films are not about the settings they take place in. However, there is an expectation from audiences that the production minimally depict settings realistically. If not, it takes you out of the film or TV show. As if her statement couldn’t get any worse, Saldana asserted that the film could have featured women of any race or ethnicity. Her words carried a double meaning: not only did the ethnicity of the characters not matter, but also of the actors playing them, thus giving herself and her costars a pass for their participation in this lazy piece of representation.

Here’s the thing: she’s wrong. Race and ethnicity do matter, specifically if the project goes out of its way to promote itself as an Identity Piece. You can’t set a movie in Mexico or Hawaii with key set pieces specific to those places and say that it’s a “universal story” that actors of any “close enough” race can portray. Hollywood’s refusal to approach the racial implications of their casting choices with any sort of nuance is contributing to declining media literacy. When people now consume media so uncritically, it is all the more important for writers and casting directors to adjust stories to who they cast in this era of remakes and adaptations. If they’re uninterested in adding nuance to the characters they randomly decide to race-swap, then frankly I’d rather them stick to the canon.

Or better yet, shelf the project altogether.

Thinness/petiteness fits within this paradigm as well, which Nani definitely WAS NOT. That girl was built like a brick house. Those thighs??? It’s also upsetting that they didn’t seem to care about that characterization either.

….wherein she wore Blackface and a fake big nose to look more like Nina.

I'm also so confused why they are remaking HP in general. Hoo boy.

Great post. I don't know how i never knew before, but i had no idea zoe saldaña was cast as nina simone... and they literally darkened her skin... hollywood is a mess, my god.